Maduro captured: Venezuela’s oil future at a crossroads

The overnight capture of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro by US forces marks a defining moment for the country’s oil sector and for global heavy crude markets. While immediate price reactions are likely to be measured, the broader implications for Venezuelan exports, production, and geopolitical alignments are far-reaching.

Key Takeaways

- US forces captured Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and his wife overnight, marking a dramatic escalation in military operations.

- Crude prices are likely to firm in the short term, though the market reaction will likely be contained by global oversupply.

- Venezuelan production could fall by 200 kbd to below 700 kbd by February if the US maintains its blockade.

- However, if sanctions are lifted, output could rise by 100-150 kbd to 950 kbd within three months, reaching 1.1–1.2 Mbd by end-2026 and up to 1.7–1.8 Mbd by 2028.

- Buyers will shift: China and Cuba face near-term supply risk, while the US will continue importing; India and Spain could return as key offtakers.

- Iran and Russia stand to gain short-term market share among Chinese teapots if Venezuela normalises relations and pivots toward Western markets.

Market & Trading Calls

- Venezuelan exports to remain constrained short-term, particularly to China and Cuba. Shipments to the US are expected to continue uninterrupted.

- Flat price bullish short-term, but bearish medium-term if a political transition unlocks 300-400 kbd of additional supply by end-2026.

- Bullish heavy sour differentials for Iran, Russia in the short-term, and LatAm grades like TMX, Napo, Marlim, and Roncador into Eastern Asia. Cuba will seek Mexican and Russian grades as replacements.

1. What just happened, and how will markets react?

The US military captured President Nicolás Maduro and his wife overnight, marking the clearest shift yet from sanctions enforcement to regime change. The move follows the seizure of Venezuelan cargoes and intensified maritime pressure in the Caribbean.

Caracas is unlikely to mount a meaningful military response as the Venezuelan government has limited retaliation options, even more now that Maduro has been captured. This means any price bump will be limited and markets will refocus on oversupply shortly thereafter. Over time, Washington and Caracas are likely to negotiate for the return of political opponents such as Maria Corina Machado. Until then, the US is likely to keep its pressure intact.

Crude markets will likely open higher on Sunday night as traders price in uncertainty and risk of near-term supply disruption. Prices could initially jump by 3-5%. That said, the upside is set to remain contained. Venezuela accounts for just 1.6% of global seaborne crude exports. With net length around 3.1 mbd in Q1 2026, the market remains broadly well-supplied. Any price bump will be limited and markets will refocus on oversupply shortly thereafter.

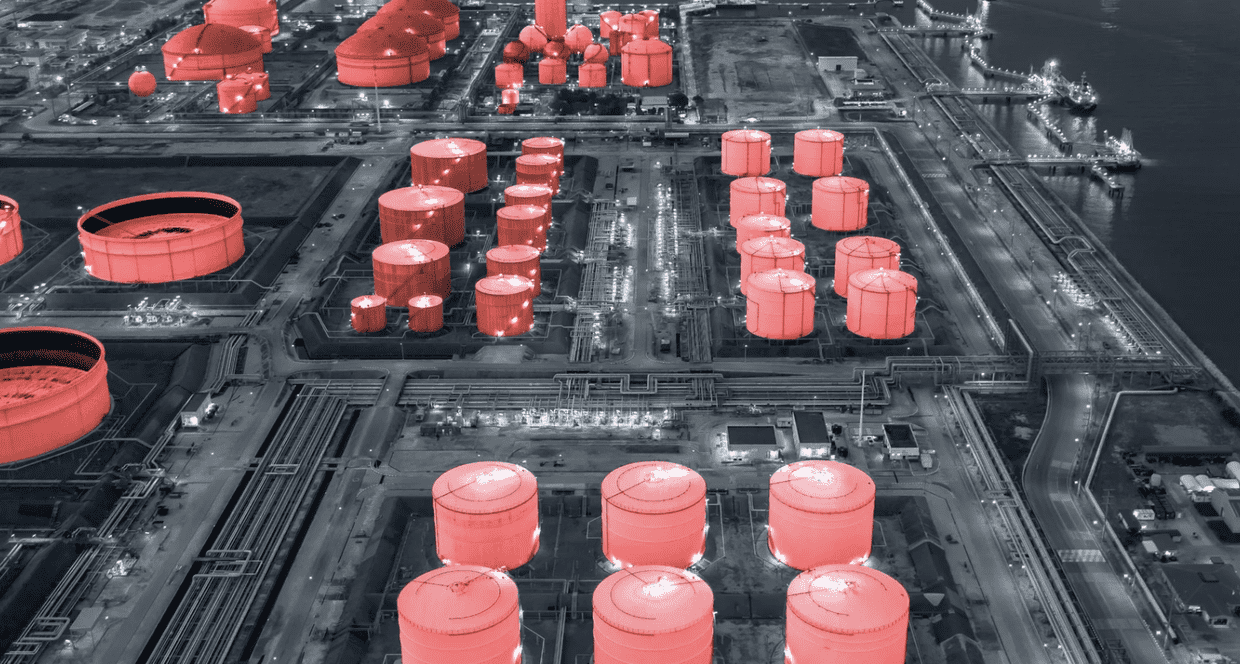

2. What impact on exports? How many vessels have departed Venezuela since the US blockade began on 10 December?

PDVSA exported roughly 765 kbd in recent months, with nearly 75% bound for China. Of these, an estimated 300 kbd is at risk if the US maintains its blockade. While Cuba continues to receive modest volumes (~14 kbd), Kpler data shows only 1 of 5 tankers engaged in the Cuba route is currently sanctioned, suggesting these flows could continue. However, any Venezuelan cargo heading to Cuba would be scrutinised, increasing risks for shipowners. Likewise, Chevron’s upstream flows to the US (~145 kbd) appear immune from disruption. These heavy barrels remain crucial for USGC refiners and are unlikely to be blocked under current political dynamics.

Since the US ratcheted up pressure in early December, Venezuela has been loading crude without any interruption, but exporting the crude is a different story. We are seeing crude being shipped to the US with no issues. However, VLCCs that have loaded and are heading to China are idling in Venezuelan waters due to the US military presence in the region.

Since December 10, 25 cargoes have loaded at Venezuelan terminals aboard 22 tankers. Of these:

- 6 vessels have headed to the US, mostly under Chevron’s sanctions waiver, indicating that Venezuelan shipments to the USGC have continued despite the pressure build-up on Caracas.

- The remaining cargoes are tied to sanctioned tankers, many of which have gone dark and drifted toward floating storage.

Our data shows:

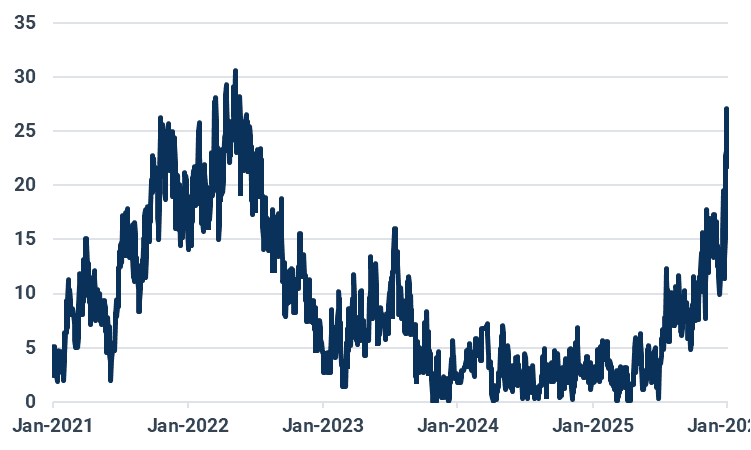

- Floating storage has surged to 23.6 mbbls, a multi-year high, up from 12.5 mbbls on 10 Dec.

Venezuela oil in floating storage, mbbls

Source: Kpler

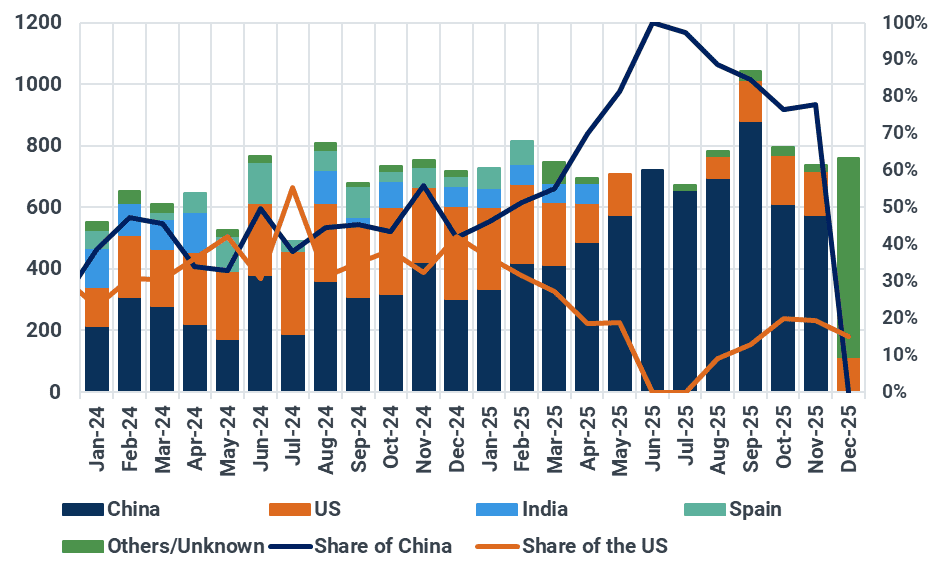

- Crude exports fell to just 300 kbd during the final week of December, compared to ~960 kbd in early December. Exports to the US averaged 115 kbd in December, down 28 kbd m/m. Those to China fell from an average of 688 kbd in Sep-Nov to zero in December.

Venezuela oil loadings and exports by destination, kbd

Source: Kpler

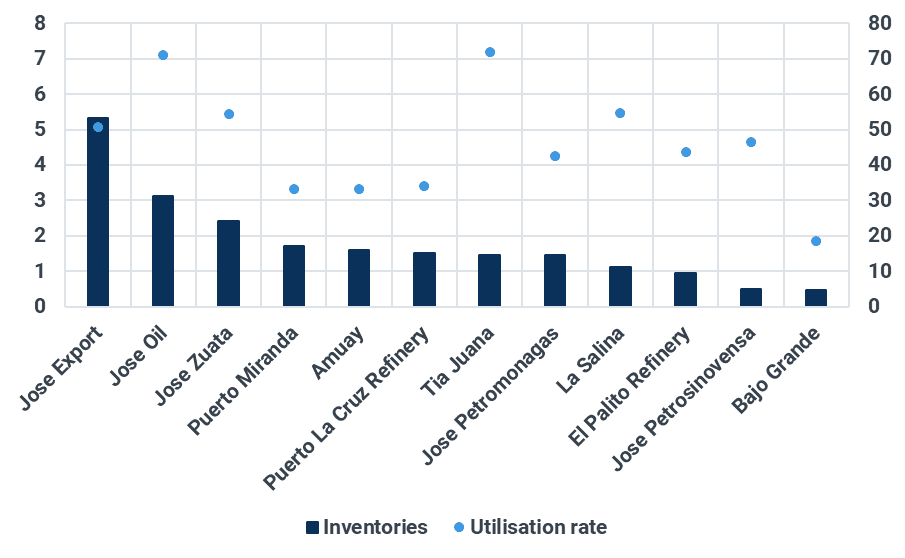

3. What’s the short-term production outlook if disruption continues?

Production has already started dropping from 870 kbd to ~800 kbd. PDVSA is now using vessels to store unsold barrels. However, if the US maintains its blockade and PDVSA pivots to onshore storage to absorb unsold barrels, Orinoco Belt shut-ins will accelerate and output could fall from 795 kbd currently to 600–700 kbd by February. With an effective onshore storage buffer of 15–20 Mbbl, production can be sustained at current levels (~795 kbd) for another 6-8 weeks.

Venezuelan onshore oil inventories (Mbbls, LHS) and utilisation rate by installation (%, RHS)

Source: Kpler

Diluents are an additional key constraint. Four Russian naphtha cargoes arrived in December, all after Dec. 10 but a 500 kb cargo of naphtha aboard the was heading to Venezuela and made a u-turn on 24 Dec back towards the MEDGarnet. Another 320 kb cargo aboard the Sea Maverick has been idle off Guyana since 13 Dec. On the other hand, there were no new US naphtha departures since Minerva Astra arrived on 23 Nov.

If PDVSA cannot import condensate or naphtha as a blending component, production could drop to as much as ~200 kbd by Q2 as we estimate the country still holds around two months of naphtha inventories.

4. What production upside is possible if sanctions are lifted and there is a political transition?

While there is mostly short-term downside to Venezuelan production, there is also an upside of roughly 100 kbd within three months in the event of a negotiated transition of power. This could be achieved primarily via increased imports of naphtha to use at upgraders in the Orinoco Belt and via workovers in the Maracaibo basin.

Contrary to some market narratives, lifting production capacity from today’s 900 kbd toward 2 Mbd by simply reactivating idle capacity is not a quick operational fix. Venezuela last produced at that level nearly nine years ago, in 2017, and the prolonged decline, chronic underinvestment, and harsh operating conditions in the Orinoco Belt, where heat, humidity, and corrosion severely degrade infrastructure, mean that meaningful capital expenditure will be required to restore wells, pipelines, processing units, and power systems to reliable operation.

Assuming a US-backed transitional government and full sanctions relief (we estimate current production at ~800 kbd):

- Short-term upside: 100-150 kbd or a return closer to 1 mbd could be achieved within three months through: reactivation of Petrocedeno’s damaged upgrader (Merey) and workovers in the Maracaibo basin (Boscan grade).

- By end-2026: upside of 300-400 kbd to 1.1–1.2 mbd capacity via mid-cycle investment and repairs at the functioning Petropiar upgrader operated by Chevron, as well as further workovers in the Maracaibo basin.

- By 2028: upside of 800-900 kbd to 1.7–1.8 mbd capacity, contingent on major upstream capex and JV terms, assumes the resumption of Petromonagas and Petrororaima upgraders.

However, ramping up to 2 mbd and above is unlikely without sweeping reforms at PDVSA and new upstream contracts signed with foreign companies. A political shift away from a left-wing government in Caracas would arguably reduce the likelihood of renewed engagement by Chinese SOEs, while potentially encouraging Western firms familiar with Venezuela’s upstream sector, including Chevron, Repsol, Maurel & Prom, and Eni, to return.

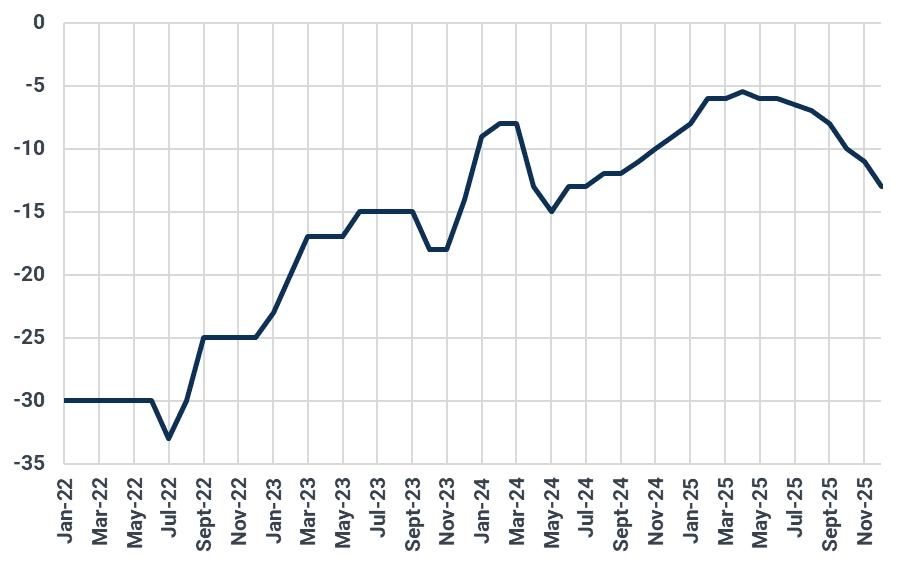

5. Who could the future buyers be for Venezuelan crude?

Such a pivot would also reshape the buyer landscape. US Gulf Coast refiners, which have been structurally short heavy-sour barrels, would be prime candidates to absorb growing Merey flows, particularly as Citgo’s ownership transitions to Amber Energy. This would challenge China’s teapot refiners, who have ramped up Venezuelan imports to ~400 kbd in 2025, and Cuba, which imported 11 kbd YTD. Both face a sharp reduction in access should PDVSA shift to purely commercial sales.

If sanctions are lifted, buyers will rebalance:

- US Gulf Coast refiners will reclaim volumes, especially with Citgo’s assets now sold to Amber Energy. The USGC imported 650 kbd of Venezuelan crude in 2013-2015, an upside of ~500 kbd compared to now.

- India and Spain, former large offtakers, are also likely to return, with a potential around 100-150 kbd.

- China's teapots, while currently dominant (~400 kbd), would lose preferential access if Caracas moves to commercial pricing.

6. What happens to Cuba and China in the near term?

- Cuba imported 16 kbd from Venezuela in 2025, mainly for the Cienfuegos refinery. These barrels are politically driven and could stop entirely. With Cuban oil inventories at just 360 kb, power rationing risks are high. Russia and Mexico may step in, but neither offers a perfect crude quality match.

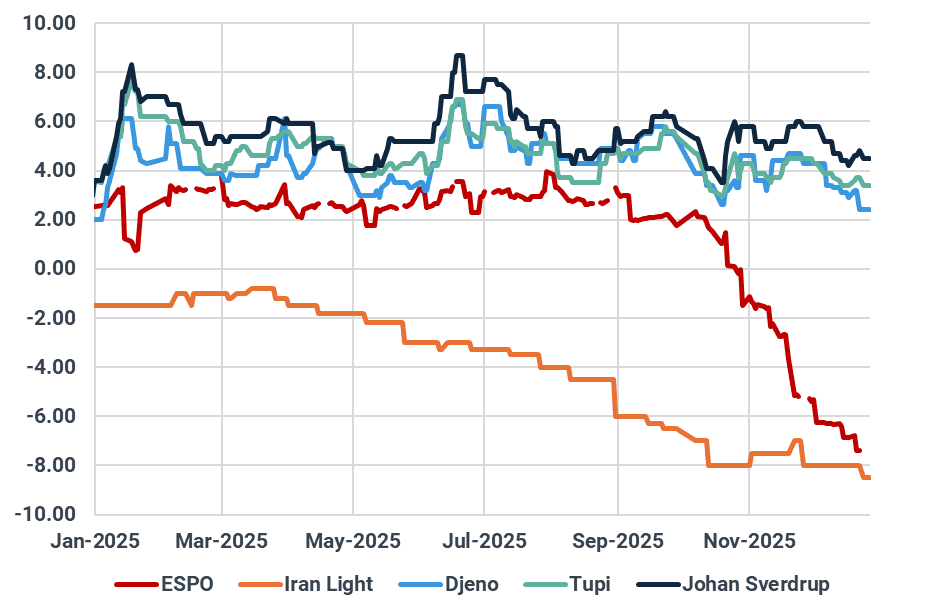

- China’s teapots will likely pivot to Iran Heavy and Urals, both of which offer pricing flexibility. A like-for-like solution would be to turn to other Latam heavy sours or Canadian crude, but these may come too expensive (TMX is currently assessed at -$5/bbl against ICE Brent in Eastern Asia, while Merey’s discount is around $15/bbl).

7. What are the implications for Iran, Russia, and heavy sour markets?

Sanctioned competitors like Iran and Russia will also be impacted. Ironically, although the countries are losing a political ally with Maduro, less Venezuelan barrels in Asia means less competition in the short-term. Demand for Iran Heavy and Urals in China will boost as these represent the second source of cheap sour crude to teapots after Venezuela’s Merey. For buyers looking for a like-for-like quality replacement, they will go for heavy sours from Latin America and Canada, also boosting their differentials in the short-term.

- Short-term bullish for sanctioned suppliers:

- Iran and Russia gain share in China and their differentials gain.

- TMX, Napo, Marlim, and Roncador differentials likely to firm on tightening heavy sour supply in Asia.

- Medium-term bearish for Iran/Russia if Venezuela returns:

- A normalised Venezuela would see higher volumes of heavy sour crude available in the market by the end of 2026, weighing on competing grades.

Selected grades diffs against ICE Brent, DES Shandong, $/bbl

Source: Argus Media

Merey diffs against ICE Brent, DES China, $/bbl

Source: Kpler

Want market insights you can actually trust?

Kpler delivers unbiased, expert-driven intelligence that helps you to track critical crude oil market developments for your own analysis. Our precise forecasting empowers smarter trading and risk management decisions.

Unbiased. Data-driven. Essential. Request access to Kpler today.