~9 mbd at risk: why Mideast Gulf Arab states lobbied to prevent a US strike on Iran

Intense diplomatic engagement by Mideast Gulf Arab states reportedly played a material role in convincing the U.S. administration not to proceed with direct military strikes against Iran, despite recent unrest and protest-related fatalities in Tehran.

According to regional media reports, several Gulf capitals warned President Trump of the potentially catastrophic consequences of a military confrontation, not only for regional stability, but also for global energy security.

Beyond geopolitics, this was about energy security

There are multiple geopolitical and strategic reasons why U.S. strikes on Iran carry high risks for the region: the danger of conflict spillover into neighbouring territories, domestic political destabilisation, and the economic shock such escalation could trigger at a time when Gulf states are investing heavily in long-term transformation agendas such as Saudi Vision 2030.

Over the longer term, a more open, unsanctioned Iran would likely re-emerge as a serious competitor for Arab stades in terms of capital flows, tourism, and regional influence.

But for energy markets, the message from Gulf capitals was more immediate: protect the uninterrupted flow of hydrocarbons through the Mideast Gulf. Energy security considerations were front and centre.

Strait of Hormuz: the region’s strategic vulnerability

Mideast Gulf Arab producers remain uniquely exposed to disruption in the Strait of Hormuz, a chokepoint through which roughly 15 mbd of seaborne crude and around 20% of global LNG volumes transit daily.

Officials reportedly feared that U.S. strikes on Iranian targets could have triggered Iranian retaliation against Gulf oil and gas infrastructure including offshore platforms, processing facilities and export terminals. This is likely why Riyadh and Doha reportedly insisted they would not allow U.S. fighter jets to use their airspace.

Beyond direct strikes on infrastructure, other potential retaliatory pathways include: harassment or temporary closure of the Strait of Hormuz and escalation around alternative maritime chokepoints, notably the Bab el-Mandeb, threatening Red Sea trade routes and tanker flows.

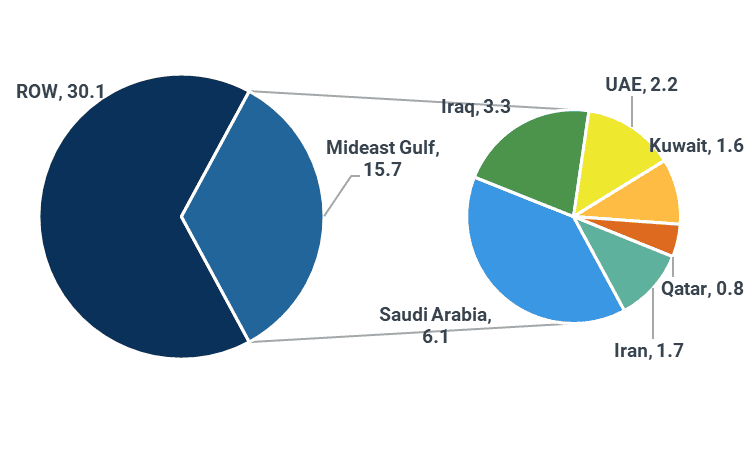

Global seaborne oil trade and share passing through the Strait of Hormuz in Q4 2025, mbd

Source: Kpler

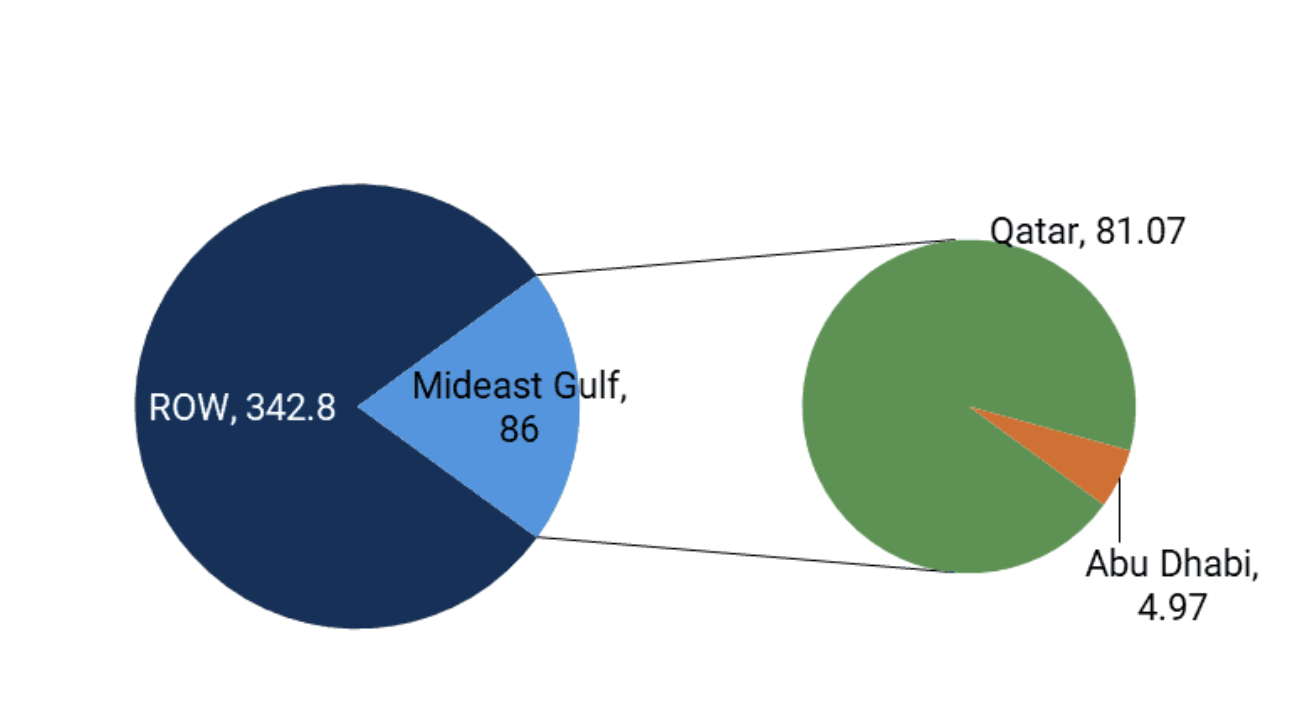

Global LNG trade and share passing through the Strait of Hormuz in 2025, Mt

Source: Kpler

Why Iran has limited incentive to close Hormuz, but the risk still matters

These concerns persist even though Tehran had not openly threatened to close the Strait this team, a threat it is often quick to raise when under pressure.

In practice, a full closure would be politically self-destructive for Iran. Around 40% of China’s seaborne oil imports pass through Hormuz, meaning any sustained disruption would not only alienate Gulf neighbours, but also risk undermining Beijing, Iran’s key crude buyer and political backer.

Still, markets do not require a formal “closure” to reprice risk. Limited disruption, shipping intimidation, insurance shocks, or temporary restrictions would be enough to tighten prompt balances and lift crude risk premia.

Oil and gas flow diversions are limited

Regional producers do have some capacity to bypass Hormuz, but rerouting potential is capped by existing infrastructure. Two pipelines matter most:

Saudi Arabia: East–West Pipeline (to the Red Sea)

Saudi Arabia’s East–West pipeline links the Abqaiq production hub in the Eastern Province to Yanbu on the Red Sea. Capacity stands at around 7.0 mbd, following expansions completed in recent years. The pipeline supplies Saudi refineries on the west coast, including:

- Yanbu (240 kbd)

- YASREF (430 kbd)

- SAMREF (400 kbd)

- Petro Rabigh (400 kbd)

- Jizan (400 kbd) (not directly linked, but supplied via Yanbu/Muajjiz terminals connected to the system)

On top of domestic refinery supply, the pipeline also supports west coast exports, which averaged ~770 kbd in 2025 YTD. We estimate the pipeline is currently operating at roughly 35% utilisation, implying around 4.5 mbd of theoretical spare capacity. In practice, however, diversion capability remains constrained relative to the roughly 6 mbd typically exported from the eastern coast, particularly during periods of strong refinery intake and sustained west coast exports.

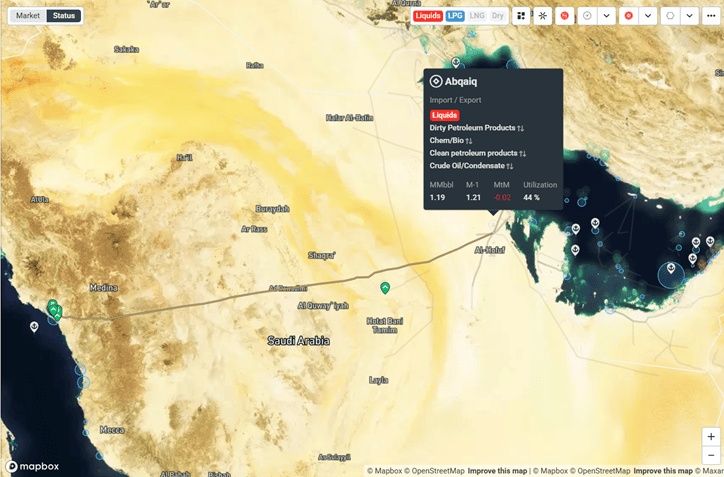

Saudi East–West pipeline: 7 mbd capacity, ~35% utilisation

Source: Kpler, Mapbox

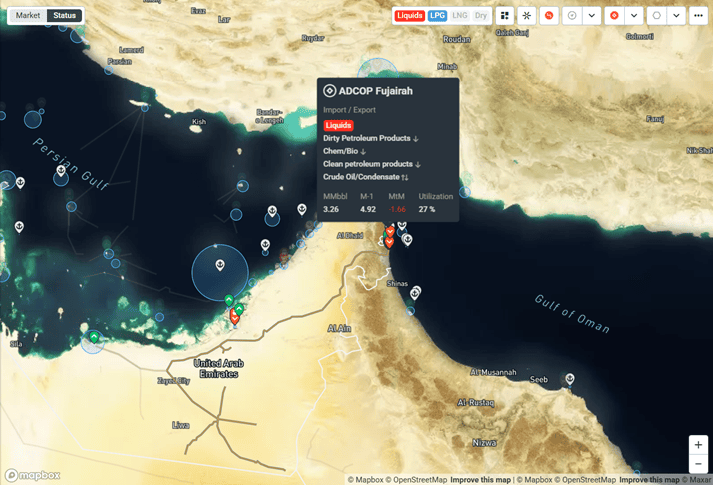

UAE: ADCOP (to Fujairah / Gulf of Oman)

The UAE’s ADCOP links the Habshan pumping station in onshore Abu Dhabi to the export terminal at Fujairah, outside the Strait of Hormuz. The pipeline has capacity of 1.5 mbd, potentially slightly higher in the short term through operational optimisation.

Current export patterns suggest around 75% utilisation, leaving roughly ~400 kbd of incremental capacity that could, in theory, redirect Murban crude away from Hormuz exposure.

ADCOP: 1.5 mbd capacity, ~75% utilisation

Source: Kpler

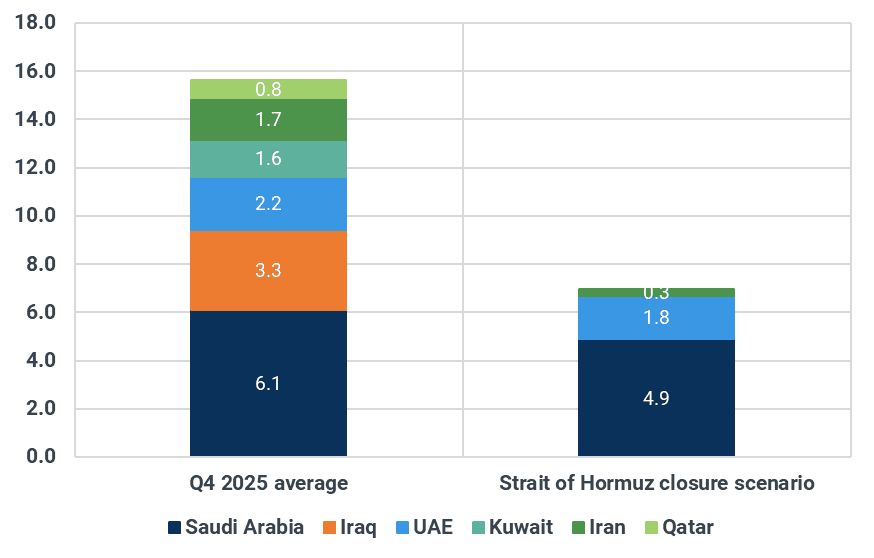

Bottom line: even with maximum diversion, ~9 mbd remains exposed

Even under a high-stress scenario where both pipelines are fully utilised, a large share of Gulf exports would remain structurally exposed to Hormuz flows. Critically, Kuwait (~1.57 mbd in Q4) and Southern Iraq (~3.36 mbd) have no alternative export corridor outside Hormuz. That leaves roughly ~9 mbd of crude supply structurally at risk in the event of major escalation, equivalent to around 9% of global oil demand.

Crude/condensate flows from the Mideast Gulf, mbd

Source: Kpler

This is precisely why a strike on Iran carries a fundamentally different market risk profile than pressure campaigns elsewhere (including Venezuela): the Mideast Gulf’s export system is globally systemic, and the ability to reroute is limited.

Want market insights you can actually trust?

Kpler delivers unbiased, expert-driven intelligence that helps you to track critical crude oil market developments for your own analysis. Our precise forecasting empowers smarter trading and risk management decisions.

Unbiased. Data-driven. Essential. Request access to Kpler today.