US - EU trade deal is finalized; ambitious EU energy purchase target will be hard to meet

The latest US - EU trade deal sets lofty energy import goals, but logistical, legal, and market constraints raise doubts about feasibility.

Market and Trading Calls

- We Have a Deal: The US – EU trade deal, minted over the weekend of July 26th, establishes a 15% US import tariff on most EU goods, excluding steel, and aluminium, which will remain at 50%. The EU also committed to $600bn in new foreign direct investment, although this is non-binding.

- Energy Purchase Target: As part of the deal, the EU agreed to purchase $250bn/year of US energy exports, a target that appears out of reach under current market conditions. In 2024, total EU imports of US oil, LNG, LPG, and coal amounted to roughly $80.5bn.

- Oil: In 2024, EU purchases of US oil managed to finish at $53bn. In our view, the EU could realistically add another 250 – 300 kbd in oil imports from the United States if exporters shifted away from Asia. This would add another $6 - $7bn in total US to EU oil trade, depending on the direction of WTI.

- LNG: Based on our price forecast, EU LNG purchases from the United States will amount to $37 - $41/bn per year through 2025 and 2026, respectively, up from $20bn in 2024. This factors in the loss of Russian volumes.

- LPG & Coal: these commodities play a much smaller role in the US to EU energy trade. In 2024, LPG ($3.4bn), and coal ($3.95bn) accounted for less than $10bn combined. This is likely to decline in 2025 amid weak coking coal prices.

Market Analysis

The EU will find it difficult to meet commitments to purchase $250bn/year in US energy commodities.

A freshly minted US – EU trade agreement, finalized over the weekend of July 26th, largely mimics the deal forged with Japan a week earlier, with some new requirements thrown in. The deal raises US import tariffs on EU goods excluding autos, steel and aluminium, to 15%, up from 10%. Notably, the import tariff on autos and auto parts was cut to 15%, down from 25 – 27.5%. Tariffs on steel, and aluminium remain in place at 50%. Pharmaceuticals, semiconductors, aircraft components, and other critical materials remain outside tariff implementation. The EU has also committed to an additional $600bn in foreign direct investment into the United States, albeit the details around implementation remain unclear and are non-binding.

Americas trade deal with the EU establishes a framework for US trade negotiations we believe will persist moving ahead. The White House looks to be settling on a tariff rate, excluding certain sectors, at roughly 15%. In addition, the ability to get a final deal over the line will require non-binding commitments for new foreign direct investment. In our view, this dynamic creates clear inflationary pressure for America over the next 8 - 12 months.

The announced deal also outlines an aggressive EU commitment to purchase $750bn in US energy exports over three years, or $250bn annually. Kpler Insight views this purchase commitment as unrealistic under current market conditions. For context, total EU-27 purchases of US oil, LNG, LPG, and coal in 2024 was roughly $80.5bn, meaning the EU will find it hard to meet the $250bn goal, even when considering the possibility that Europe lifts the pace of imports from the US.

Beyond the technical and commercial challenges, the EU cannot legally mandate domestic refiners to purchase oil or LNG from the US unless such a requirement is codified into law, which would likely face legal and market challenges under EU competition and procurement rules. Given that most European refiners are now privately owned and commercially driven, their purchasing decisions are guided primarily by economics, such as crude compatibility, freight costs, and refining margins rather than political pledges. Without financial incentives or regulatory mandates, a voluntary shift toward US supply would depend on clear commercial advantages.

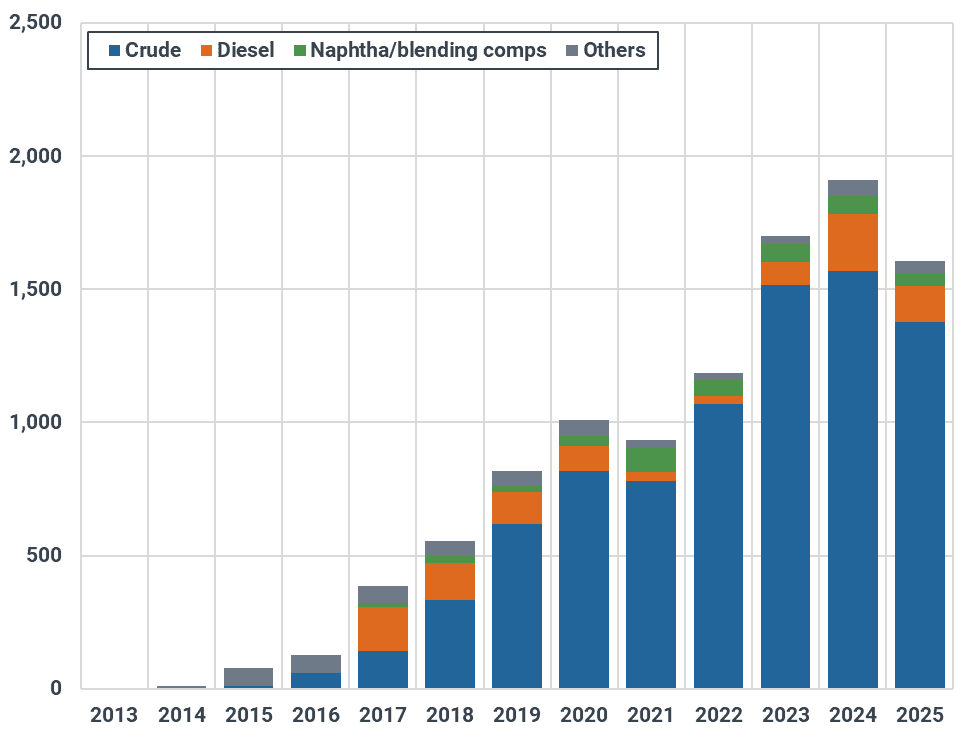

In 2024, EU imports of US crude, and products amounted to $53 billion.

In both value and volume terms, crude oil and refined products account for the bulk of US energy traded into the EU-27. So far this year, the bloc has imported around 1.6 Mbd of oil from the US, primarily crude (86%), along with diesel (8%) and lighter products. This marks a decline from 2024, when EU-27 imports reached nearly 1.9 Mbd, including 1.53 Mbd of crude, for an estimated annual value of $53 billion.

Yearly EU-27 Seaborne Oil Imports from the US by Product Type (kbd)

Source: Kpler

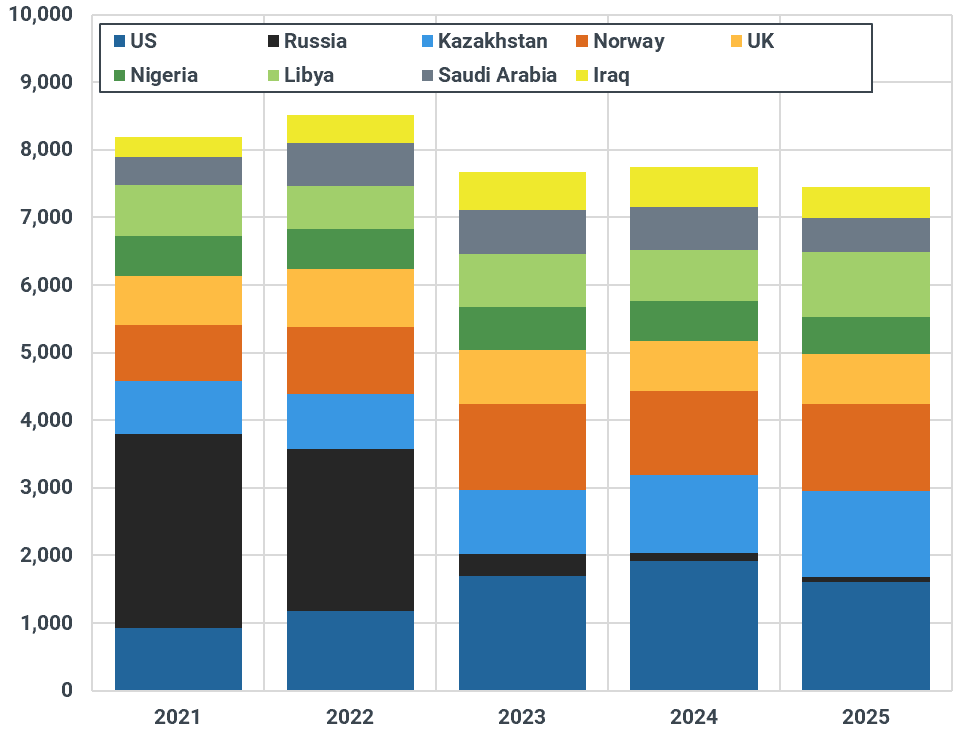

In 2024, the US accounted for 13.4% of total EU-27 oil imports, and 11.4% year-to-date. This is already a significant share. Since the start of the Russia-Ukraine war in 2022, the EU has sharply reduced purchases of Russian crude and products, opening the door for the US to become its top oil supplier. On the other side of the trade, the EU-27 represented 28% of total US oil exports in 2024 and was by far the largest destination for US crude, receiving 1.53 Mbd, or 39% of total US crude exports.

Yearly EU 27 Seaborne Oil and Product Imports by Selected Origin (kbd)

Source: Kpler; only selected origins are included

In theory, the US could more than triple its oil and product exports to the EU to meet the trade deal's ambitious value target, holding all other trade flows constant. However, this would require a near-total redirection of US oil flows toward Europe, at the expense of strategic ties with faster-growing emerging markets. Currently, over 1.3 Mbd of US crude is exported to Asia, with South Korea, India, Taiwan, and Thailand among the largest buyers. A potential US-China trade deal is also likely to include bilateral energy targets, necessitating increased flows to China. In Latin America, US refined products are vital, especially for Mexico, which sources 42% of its gasoline and more than half of its diesel from the US.

Another constraint lies in refining compatibility. Many European refiners, especially in the MED, are not designed to process large volumes of light sweet crude. Their configurations are optimised for medium sour grades from the Middle East, Russia, and fields like Johan Sverdrup in Norway. Increasing the share of light crude would reduce middle distillate yields and damage margins, particularly problematic while diesel cracks remain elevated. Additionally, long-term supply contracts with firms like Aramco and SOMO limit flexibility. European refiners cannot walk away from those volumes without triggering broader commercial risks.

A more grounded objective would be for the EU to fully phase out the remaining Russian crude in its system. Imports of Urals to Hungary and Slovakia still average around 210 kbd, while refineries in Czechia (Litvínov, Kralupy) have already weaned off Russian barrels earlier this year. Eliminating these final links appears feasible.

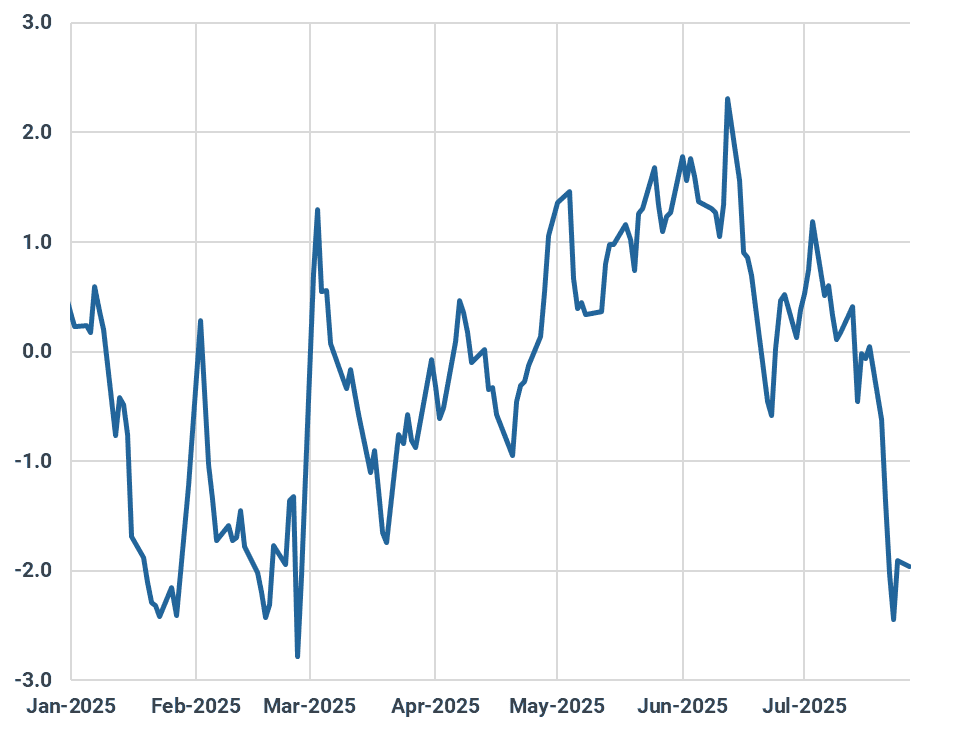

Given its quality, incremental US crude would most likely displace imports from Libya, West Africa, or the North Sea. However, despite OPEC+ gradually increasing output, WTI remains cheaper than Murban in Asia on a delivered basis, while the narrowing of the Brent-Dubai EFS spread also supports Asian buying.

Daily WTI-Murban Spread CFR Asia ($/bbl)

Source: Argus Media

In the longer term, if 20% of current US crude flows to Asia were diverted to Europe, a realistic outcome, it could unlock an additional 250–300 kbd, sufficient to fully replace the remaining Russian volumes. This is a much more achievable goal than a tripling of US oil flows to the EU and would add an additional $6.5bn in US – EU energy trade assuming a $65/bbl WTI price, or $7bn at a $70/bbl WTI price.

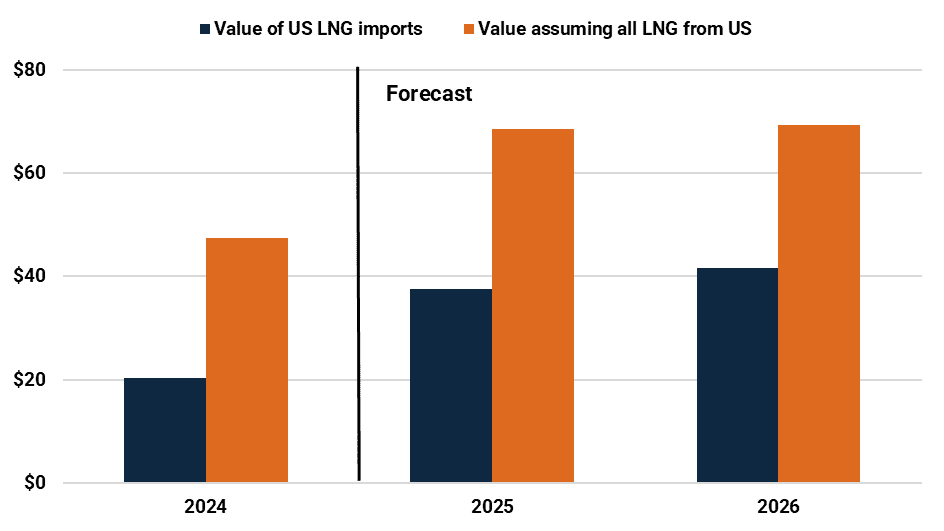

The EU is poised to add nearly $20bn in purchases of US LNG through 2025.

Based on our European natural gas price forecast of $12.4/MMBtu for 2025 and $10.5/MMBtu for 2026, we estimate US LNG exports to Europe will likely finish in a range between $37–41 billion per year, assuming a 55–60% market share position. This implies that the value of LNG imports from the US would need to increase sixfold to meet the $250bn/year purchase target, holding all other trade flows constant. Even assuming all LNG came from the US, total import volumes would still need to more than triple to reach the mentioned target.

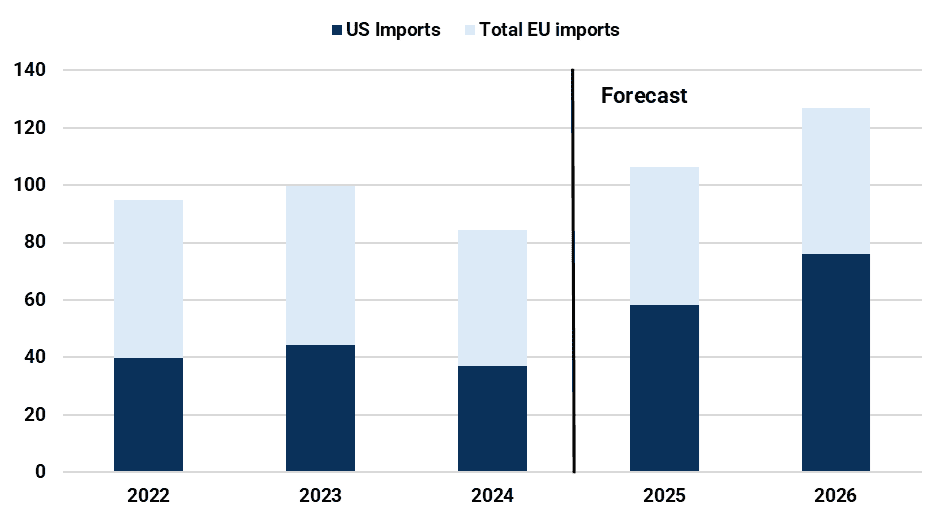

Yearly EU LNG Imports by Origin (Mt)

Source: Kpler

There could be upside in 2026–2027, when the EU’s plan to phase-out of Russian gas takes effect, but much of that upside is already factored in Kpler Insight’s forecast, with a large share of US supply offsetting losses from Russian flows, alongside higher winter demand, and storage filled at capacity by the end of October 2026. With LNG prices expected to soften amid a global supply build-out, hitting $250 billion would require volumes to rise dramatically.

Value of US LNG Imports into the European Union ($ bn)

Source: Kpler

EU purchases of US coal amounted to just $3.95bn in 2024 and will likely decline in 2025 on weaker coking coal prices.

The EU also imports volumes of US produced thermal and metallurgical coal, albeit in nominal USD terms this falls well short of nominal totals for LNG and oil purchases. In 2024, combined European imports of US thermal and metallurgical coal volumes amounted to $3.95bn. In our view, this total will likely decline 20 – 30% over 2025 and 2026 due to weak coking coal prices. We do not foresee the EU growing it’s purchases of US thermal or met coal given grade and contractual constraints.

While not falling under the energy purchases commitment, the EU also purchases significant amounts of US soybeans. We expect EU arrivals from the US to rise 20% over 2025/2026, which would push nominal purchases values above $3bn this year, up from $2.8bn last year.

Want market insights you can actually trust?

Kpler delivers unbiased, expert-driven intelligence that helps you stay ahead of supply, demand, and market shifts.

Trade smarter. Request access to Kpler today.

See why the most successful traders and shipping experts use Kpler