Venezuelan supply and export scenarios under a US military intervention

Market & Trading Calls

- Interventionalist Policy: The Trump administration’s unexpectedly interventionist foreign-policy posture has now shifted toward Venezuela, where a major US naval and Marine deployment has created meaningful optionality for large-scale strikes or limited ground operations. Caracas has responded with troop mobilizations and nationwide exercises, raising the risk of unintended escalation.

- Potential for Dialogue: Despite the military buildup, both Washington and Caracas have signaled openness to dialogue, with Trump expressing willingness to hear Maduro’s proposals and Venezuela calling for de-escalation. Any negotiations will likely hinge on narcotrafficking cooperation and migrant repatriation in exchange for potential US sanctions relief and long-term crude-trade normalization.

- Venezuelan production may stay relatively resilient: Output is centred in the Orinoco Belt and lies far from potential conflict areas, while Lake Maracaibo—around 20% of supply—is more exposed yet still an unlikely direct target. Heavy-oil reliance on steam, diluent, and upgrading adds vulnerability, though revenue needs drive the government to maximise production in any scenario. A limited strike would cut output and exports by 10–15% (to 765–810kbd and 640–675kbd), with quick recovery and potential 50–100kbd upside under a negotiated transition. A moderate invasion would deepen losses to 15–25% for production and 20–30% for exports, while a full-scale conflict would cause prolonged disruption, slashing production 25–50% and exports 30–60%.

- Supply disruptions would shift Chinese and US refiners toward alternative heavy grades across the Americas and Middle East: A loss of Venezuelan barrels, coupled with uncertainty regorging Russia sanctions, would prompt Asian refiners to source heavier Middle Eastern and Latin American grades, while US refiners would lean more heavily on regional supply and Canadian inflows. Strong production across the Americas, widening sweet–sour spreads, and record long-haul shipments to Asia would shape substitution dynamics.

Market Analysis

A surge in US force posture confronts a weakened Venezuela, raising escalation risks even as both sides signal a potential path to negotiation.

As the second Trump administration nears the end of its tenth month, one would be forgiven for underestimating the extent of White House foreign policy assertiveness. Pre-inauguration expectations leaned towards an isolationist doctrine, but the record now shows a far more interventionist reality. Continued support for Ukraine, despite the strained personal dynamic between Trump and Zelensky; a multi-week air campaign against Houthi-controlled Yemen; direct airstrike action on Iranian nuclear-related targets; and persistent backing for Israel’s war against Hamas, Hezbollah, and Iran directly all illustrate a willingness to use force across multiple theaters.

The pattern has now shifted toward Venezuela. In recent weeks, Washington has deployed a major naval presence including the USS Gerald Ford, an aircraft carrier, alongside several escort warships including the USS Winston Churchill, the USS Mahan, and the USS Bainbridge. Another dozen or so Navy ships are also in theatre alongside an Amphibious Ready Group that contains 4,000 personnel, of which more than half are Marines. While a tail event, this type of force posture provides optionality for large scale strikes or a land-based invasion.

The Venezuelans have responded to the force buildup with a mobilization of its militia and regular forces. This includes the deployment of 15,000 troops to the Colombian border, alongside additional deployments at particular points within Venezuela, albeit it is hard to assess troop size – some reports tag this at 25,000. Another 2,500 soldiers, 12 naval vessels, and 22 aircraft have participated in exercises around La Orchila island. In practice, Venezuela likely has just over 300,000 in available manpower, alongside 30 combat aircraft.

Venezuela has long faced US sanctions and diplomatic isolation over concerns around democratic governance, human rights, and its role in illicit flows of money and narcotics. The recent moves taken by the Trump administration represent a material escalation. It remains unclear whether Washington’s objective is limited to disrupting narcotrafficking networks linked to regime elites, or whether the administration is positioning itself for broader political leverage, possibly even regime pressure. Public statements from the Pentagon have been limited, leaving strategic intent ambiguous.

Recent diplomatic signals suggest Trump may be pairing military pressure with coercive diplomacy. On November 18th, reports began to surface that while Trump had not ruled out US ground forces in Venezuela, he expressed willingness to hear proposals from Maduro aimed at preventing further escalation. Caracas quickly reciprocated, stating its openness to direct dialogue and urging de-escalation. Trump is likely to press for concessions including cooperation in dismantling narcotrafficking networks and acceptance of repatriated Venezuelan migrants. In return, Washington has significant leverage to offer, including sanctions relief, tacit recognition of Maduro’s government, and potential long-term normalization of Venezuela crude flows to US Gulf Coast refiners.

Nonetheless, risks remain elevated. The rapid US military buildup along the Venezuelan border raises the probability of accidental or unintended escalation, particularly given Venezuela’s mobilization and the lack of trust between the two governments. These dynamics warrant close monitoring.

In the remainder of this month’s Commodity Geopolitics Report, we examine the potential implications for Venezuelan crude production and exports, and the balance of risks in both directions.

Venezuela’s oil recovery stalls as export patterns shift toward China

Venezuelan exports have grown steadily in recent years to around 750kbd in 2025 ytd but remain well below the peak of 2Mbd (2015). The US used to be the largest buyer of Venezuelan crude until 2018 (466kbd) but following two complete halts (from May-19 to Jan-23 and in Jul-25), US imports volumes stood at a moderate 152kbd in October. China has now become the largest buyer at more than 400kbd in 2025 ytd, while US waivers allow India (30kbd) and Spain (16kbd) to import minor volumes. Significant exports ended up in floating storage this year. Contrary to Russia, Venezuela has not managed to reroute crude exports shunned by previous buyers to alternative markets. Aside from the difficulties in navigating a complex sanctions environment, Venezuela’s upstream sector has lacked the investment and maintenance required to fully capitalize on its enormous reserves and keep production volumes at elevated pre-2019 levels. Aside from crude, Venezuela also exports 135kbd of fuel oil (2.5% of the seaborne total, mostly to China).

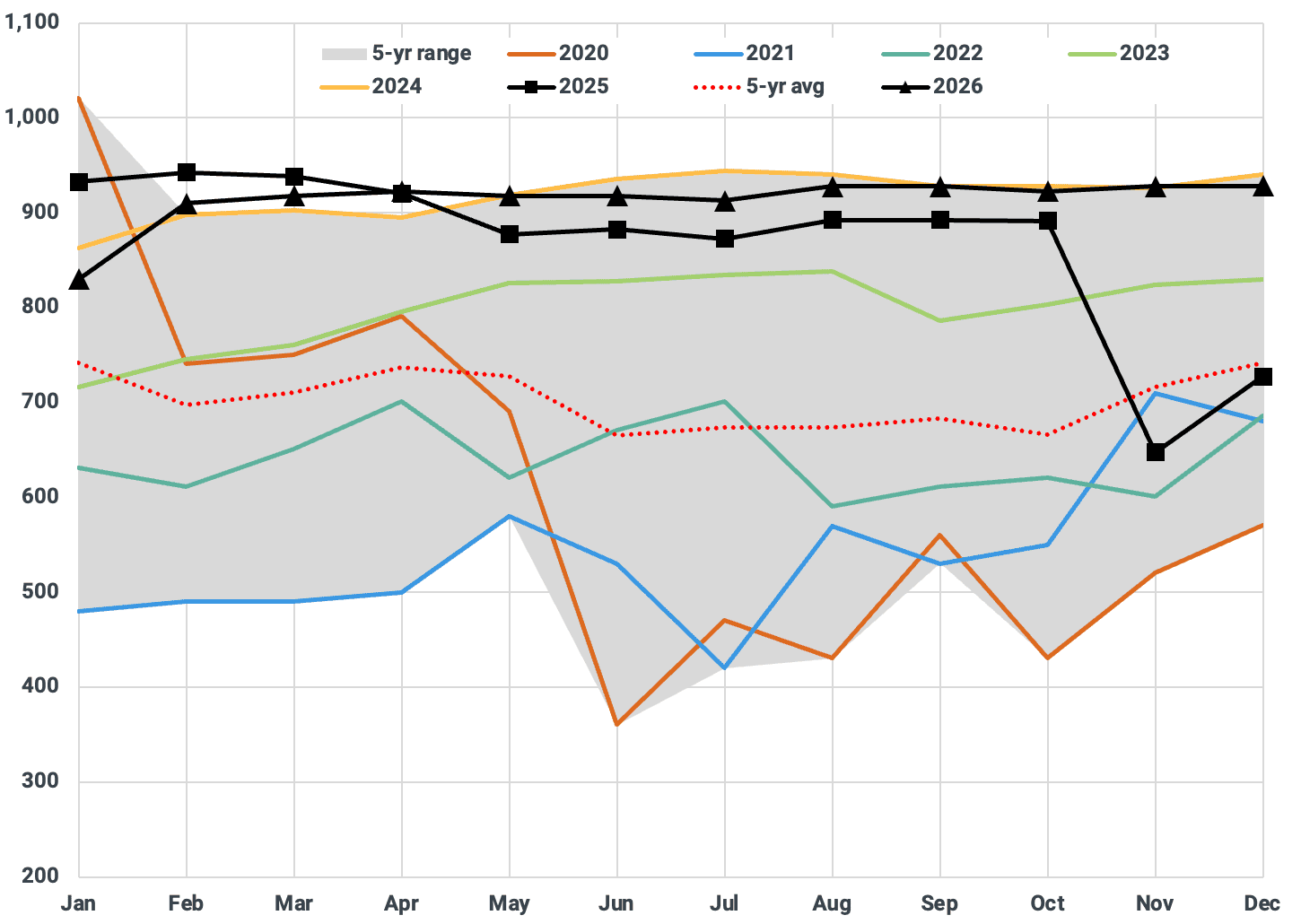

Venezuelan supply has rebounded from 2020 lows below 400kbd and stabilized around 900kbd this year, a level that our base case also expects for 2026 (see chart). JVs between PdVSA and IOCs account for roughly half of Venezuela’s crude production, with Chevron’s five JVs (Chevron interest ranging from 25.2% to 60%) making up the single-largest share. A recent string of outages at the Jose Complex resulted in 500 kbd of upgrader capacity being offline, pushing supply to a 3-year low of 650kbd this month, with a full recovery only expected by February next year (see chart). Accordingly, Merey exports will be under pressure until then, however, the elevated levels of Venezuelan floating storage, especially in Asia, have helped to buffer the short-term ramifications.

Venezuelan crude supply (kbd)

Source: Kpler

Considering the ideological divide between Washington and Caracas, it might surprise that there has been any trade at all. However, the US Gulf Coast is in structural need of heavier feedstocks that its refineries were initially designed to run on. Aside from significantly lower imports from Venezuela, a reduction in US imports of heavy Mexican crude (400kbd in 2025 ytd versus 745kbd in 2023) due to the ramp-up of the Dos Bocas refinery and the halt to US imports from Russia (combined crude and VGO imports of 300kbd in 2021) exacerbated the regional tightness in medium-heavy refinery feedstocks.

Given Venezuela’s very heavy crude production, imported diluents play a significant role when blending its domestic crude to acceptable API levels for exports. The main sources include Iranian condensate (2020-2023) and naphtha from the US (Jan-23 until May-25). However, in H2 2025, Russian naphtha has replaced most US volumes.

US military intervention scenarios: Supply losses shaped by conflict severity and heavy-oil vulnerabilities

A US invasion of Venezuela does not form our base case and a negotiated settlement appears much more likely as of November 2025. Nevertheless, we explore the potential ramifications of a military escalation. Across all scenarios, the scale and duration of Venezuela’s production and export shock hinge on factors such as physical damage to terminals and fields, the response of IOCs and JV partners, the impact of sanctions, insurance, and financial constraints, and the wider geopolitical reaction.

Overall, Venezuelan supply could turn out relatively resilient due to two factors. Firstly, the majority of the country’s production stems from the Orinoco Belt, a remote and sparsely populated region, whereas potential military action would focus most likely on the capital and the Caribbean coast. Production from Lake Maracaibo, which accounts for around 20% of the total, is therefore more at risk, however, but even there it is unlikely that attacks would target oilfields and their infrastructure. For reference, production from the Orinoco Belt is shipped from Jose Terminal, while supply from Lake Maracaibo is primarily exported via Baja Grande and Puerto Miranda. Having said that, heavy-oil production is particularly vulnerable to disruption as it requires additional inputs (steam, diluent, upgrading units) compared to conventional operations. Secondly, given that the government is almost entirely reliant on oil revenue, it will likely produce and export as much as possible in any scenario.

The main bottleneck in terms of supply is the access to diluents such as naphtha or condensate. If diluents are not imported in sufficient quantity for more than six weeks, a drop in upstream operations in the Orinoco Belt could become visible. The continuation of operations at the Jose Terminal, 250km from Caracas, is therefore key. Availability of external volumes, on the other hand, should not pose a challenge. Even though Venezuela has substituted US naphtha with Russian volumes in H2, the US Gulf Coast still produces a surplus of naphtha due to the abundance of alternative petrochemicals feedstocks. Indeed, since the end of October, three US cargoes have discharged in Venezuela.

In the case of a short, limited strike or brief invasion that avoids major infrastructure damage, production would likely drop slightly by 10–15% (to around 765-810kbd), and exports would fall by a similar 10–15% (to around 640-675kbd) due to temporary port closures and operational shutdowns. Recovery in this scenario could be relatively quick if facilities remain intact. Should a “negotiated” transition see Maduro leave, Venezuelan supply could actually increase above current levels quite fast as Washington would then grant more waivers to US producers and international buyers and would allow more naphtha to be shipped. The upside to Venezuelan supply could come in at 50-100kbd within 2-3 months.

A moderate invasion involving fighting near coastal oilfields, pipelines, storage facilities, or, most importantly, export/import terminals could trigger a sharper drop. In this scenario, production would likely fall by 15–25% (down to roughly 675-765kbd), and exports could drop by 20-30% (to 525-600kbd), as terminals and blending operations are disrupted, foreign operators suspend activity or withdraw personnel, and shipping insurers refuse coverage. Sabotage risks could also increase in this scenario.

A full-scale invasion with prolonged occupation, damage to oil and port infrastructure, withdrawal of foreign firms, and disruption of shipping or financing channels would likely result in a 25%-50% decline in supply (to 450-675kbd) and a 30-60% slump in exports (to 300-525kbd). Repairing terminals, restoring staffing, and creating a stable legal and commercial environment would require an extended reconstruction period. The international reaction would matter greatly: if major buyers such as China continue purchasing despite the conflict, exports might recover sooner; if they reduce or halt imports because of sanctions or risk, the downturn would deepen.

Substitution options for US and Chinese refiners under a Venezuelan supply shock

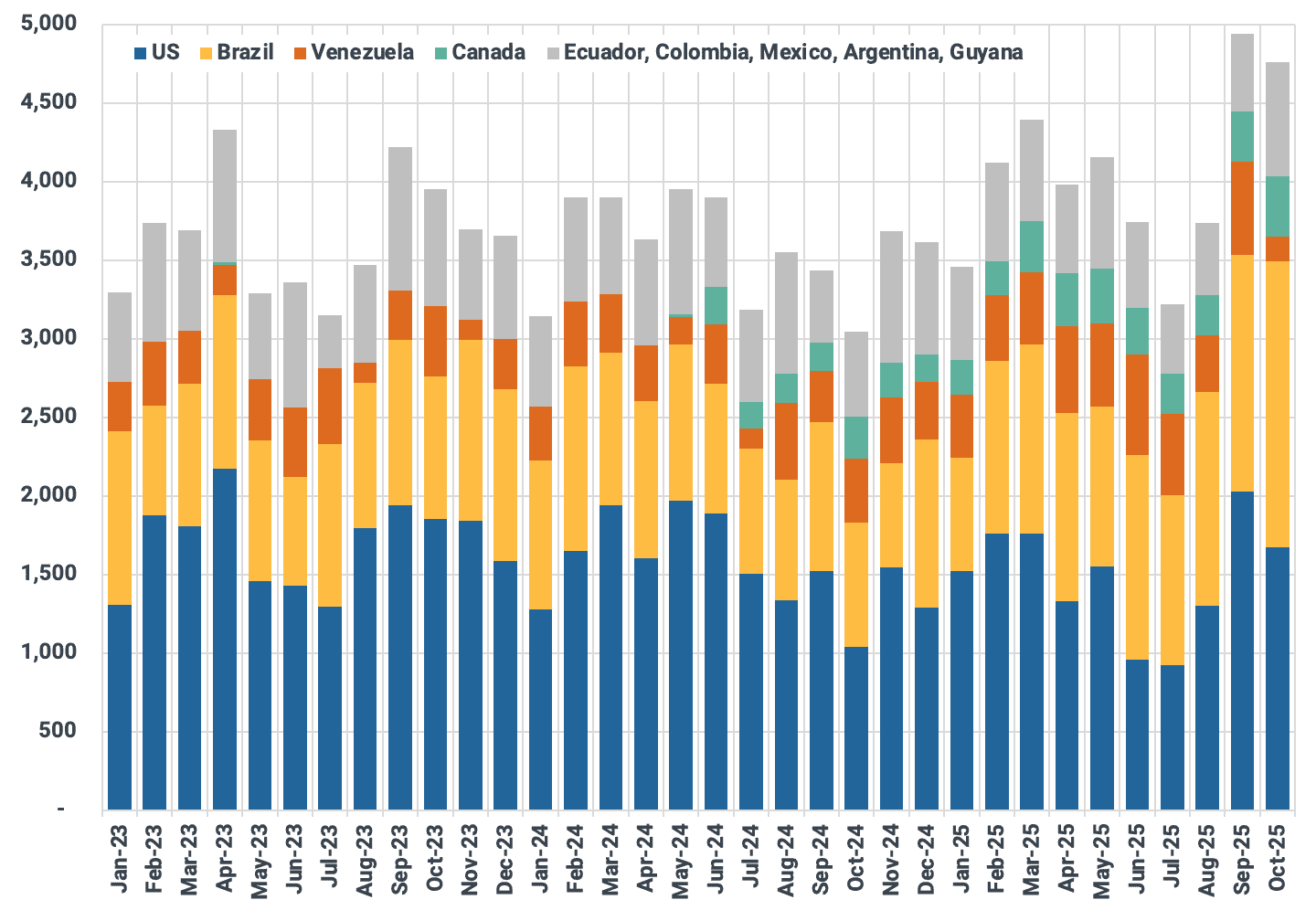

Chinese refiners: If Venezuelan supply and exports were disrupted, Chinese refiners would likely turn toward the Middle East where OPEC members, especially Saudi Arabia and the UAE, are in the process of unwinding production cuts. However, even the heavier grades such as Arab Heavy (API 28°) or Iranian Heavy (API 30°) are significantly lighter than the Venezuelan staple grade Merey (API 16°). Closer substitutes can be found in the Americas, and current quality spreads are in favor of such long-haul sourcing. While sweet-sour crude spreads are still narrow in Asia, they are wide in the US, driven by strong medium-heavy output across the Americas. This, coupled with Asian refiners facing uncertainty regarding Russia sanctions keeps demand for medium-heavy barrels of non-Russian origin high and has already contributed to record volumes of North and South American crude being shipped to Asia (4.9 Mbd and 4.8 Mbd in September and October, respectively, see chart). In this regard, Venezuela (441 kbd in 2025 ytd) ranks third behind Brazil (1.22 Mbd) and the US (1.45 Mbd), and ahead of Canada (305 kbd).

Americas crude exports to the East of Suez by origin (kbd)

Source: Kpler

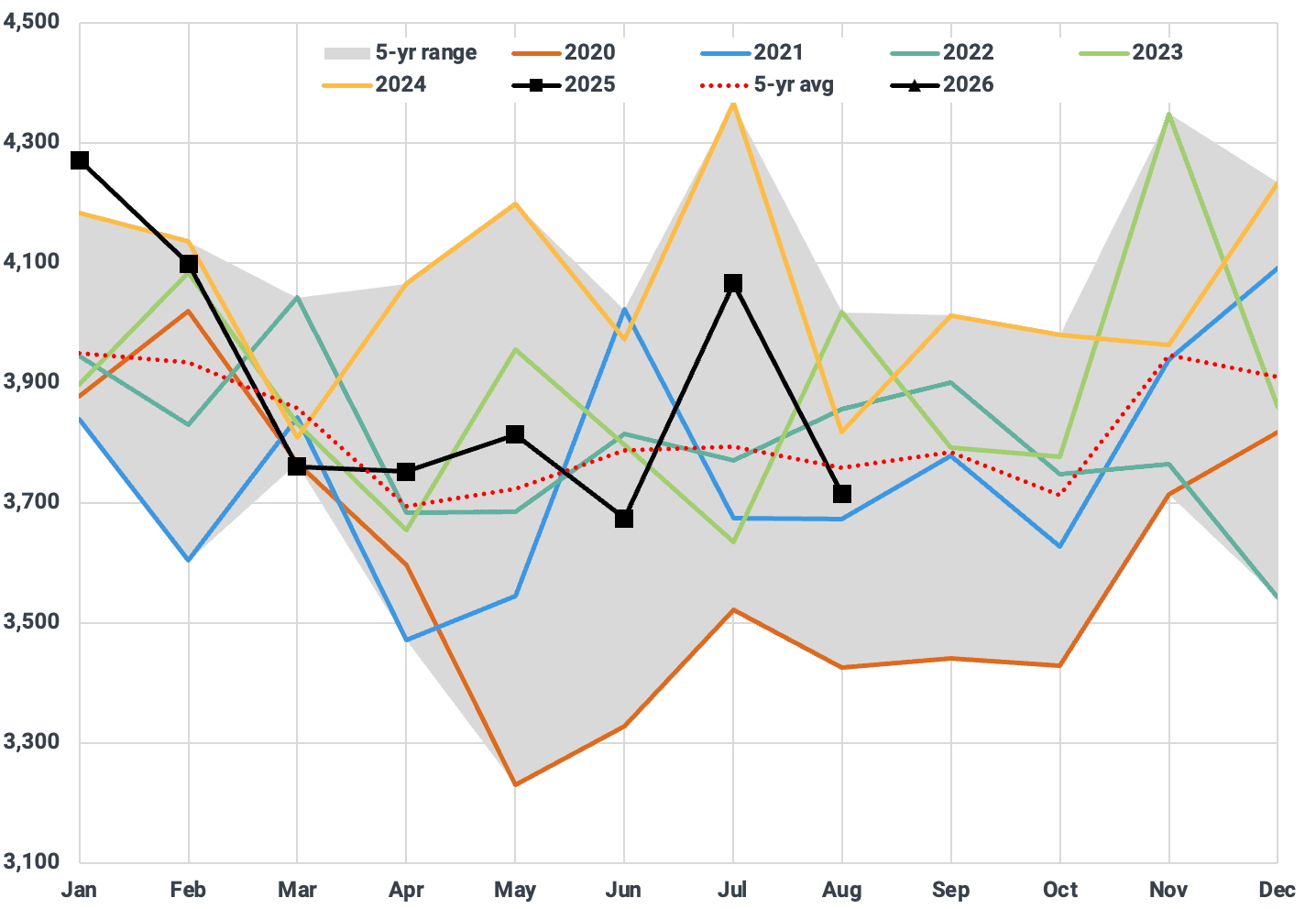

Canadian crude exports from Westridge, the TMX pipeline’s main export terminal, are on track to reach 530 kbd in November, 426 kbd of which are currently pinging Asia as their destination, both representing new highs. These elevated exports levels are being facilitated by strong Albertan crude production that has stabilized above 4.2 Mbd, near the record-high from July (4.31 Mbd). Structurally higher demand for non-Russian grades could further bolster the export economics of heavy barrels from the Americas, and according to Canadian Prime Minister Carney, an additional pipeline to Canada’s West Coast with a capacity of up to 1 Mbd is “highly likely to be proposed as a nation-building project”. In addition, Brazilian crude exports to Asia reached a new record of 1.8 Mbd in October, boosted by additional FPSOs that came online in the Santos Basin. In September, US exports to Asia recorded the second highest monthly volume of more than 2 Mbd, driven by higher flows to India and South Korea, which offset the halt in Chinese buying.

US refiners would likely initially resort to regional crude grades from the Americas. In the unlikely scenario of a US invasion, one could assume that whatever Venezuelan crude output remains would serve the needs of the regional US Gulf Coast refiners first, rather than being shipped to Asia. Higher US buying of regional heavy barrels from the Americas would automatically complicate the economics of respective long-haul shipments to Asia, turning Middle Eastern crude into the more likely longer-term replacement for Asian refineries.

While wide US sweet-sour differentials currently play in favor of US refiners and could lead to shifts in crude sourcing at the margin, the vast majority of US refiners’ crude slate is either produced domestically (light-sweet shale onshore, medium-sour grades offshore Gulf of Mexico) or imported via pipeline from Canada. In fact, US imports of Canadian crude – at 3.89 Mbd (Jan-Aug 2025) the largest country-to-country crude flow globally – provide the backbone of refiners especially in the US Midwest.

US imports of Canadian crude (kbd)

Source: Kpler calculations based on EIA

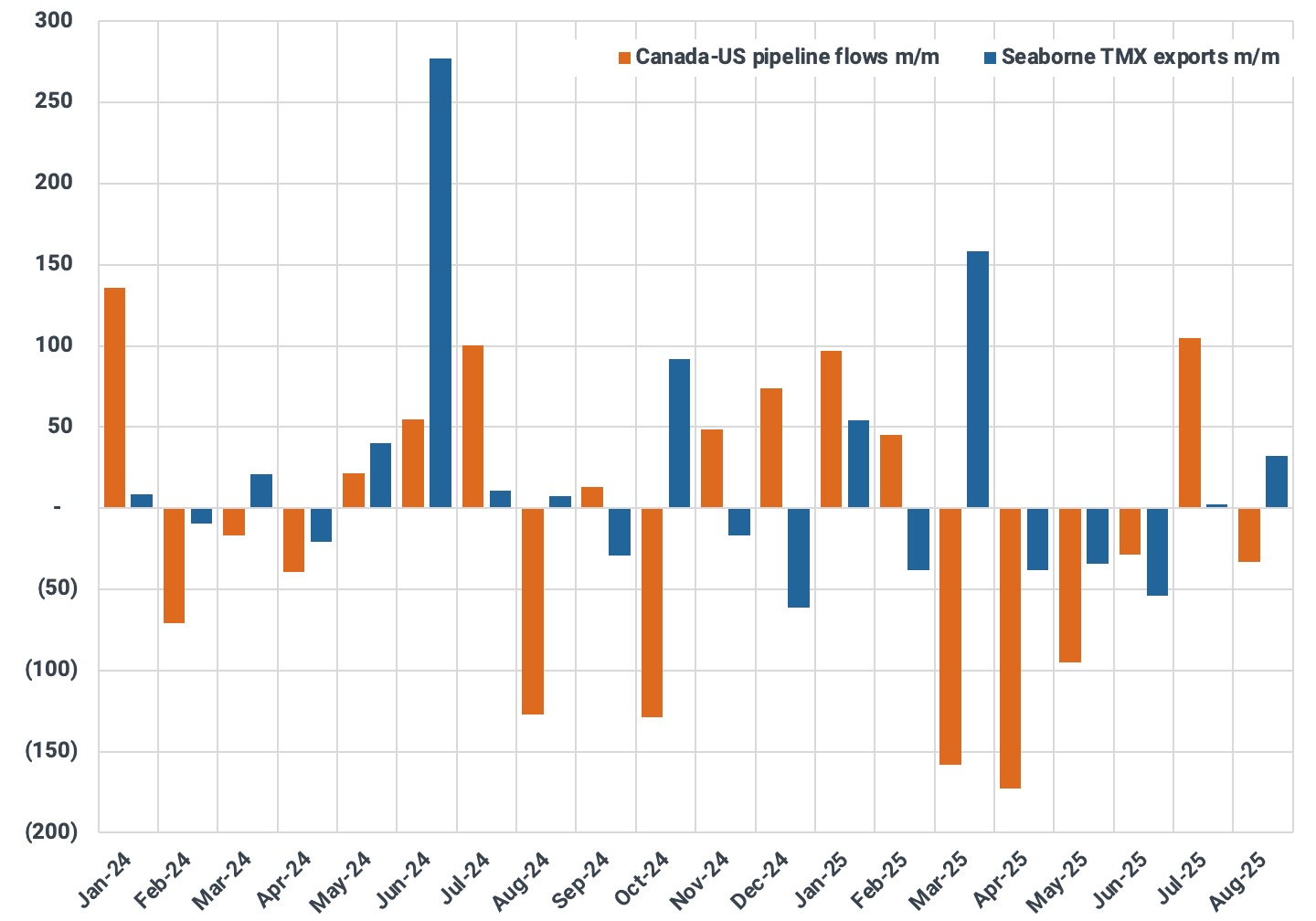

The TMX ramp-up has contributed to reduced cross-country pipeline flows, and in 2025 ytd, seaborne TMX exports rose by 200 kbd y/y, while Canada-to-US pipeline flows declined by 168 kbd y/y (Kpler calculations based on EIA data). Nevertheless, TMX’s overall impact on cross-border flows is small in the grand scheme of things, especially in light of rising Albertan crude supply. Considering that Canada-to-US pipeline flows peaked at 4.37 Mbd in July 2024, there is a theoretical upside in pipeline capacity of more than 600 kbd versus latest available data (3.72 Mbd in August 2025, EIA).

Canada-US pipeline flows m/m vs seaborne TMX exports m/m (kbd)

Source: Kpler calculations based on EIA, Kpler

The closest substitutes for Merey in terms of API and sulfur are to be found in its vicinity, namely Colombian grades such as Castilla, Apiay, Magdalena, and Mares. The US is already the main recipient of Colombian exports but could eat into Asia’s long-haul share of around 110 kbd in 2025 ytd (230 kbd in 2024). Ecuador’s Napo (80 kbd to Asia in 2025 ytd) and Oriente (45 kbd) also offer similar specifications, as does Canada’s Cold Lake Blend arriving via pipeline.

Venezuelan crude and substitutes - API and sulfur content

Source: Kpler based on various crude assays

Want market insights you can actually trust?

Kpler delivers unbiased, expert-driven intelligence that helps you stay ahead of supply, demand, and market shifts. Our precise forecasting empowers smarter trading and risk management decisions.

Unbiased. Data-driven. Essential. Request access to Kpler today.

See why the most successful traders and shipping experts use Kpler